Story by Bob Seyller, Texas Military Department Public Affairs

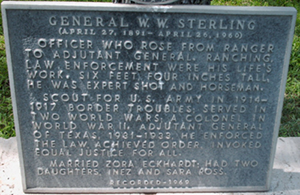

In the early days of Texas, the Rangers provided security and rule of law. However, as Texas grew, the Rangers also grew in both size and mission. During the Texas Revolution, the force formalized from a security force for settlers to well-trained soldiers and finally into lawmen delivering justice to an untamed frontier. No matter their role, it was clear: they were a military force. Nearly 100 years after the Texas Revolution, this connection would lead to a Ranger’s first term as adjutant general when Brig. Gen. William Sterling took office.

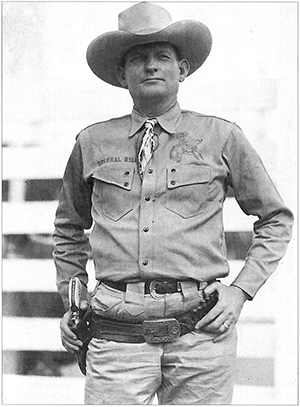

Texas Adjutant General William Sterling

Texas Adjutant General William Sterling

Born in Belton, Texas, near the turn of the century, Sterling grew up on his family’s ranch. It was there where Sterling learned how to ride, forage and shoot, before enrolling in Texas A&M University for courses in animal husbandry. Studying for two years, Sterling never attained his degree. Instead, he left to put his knowledge to use on ranches throughout Hidalgo County. Sterling had worked toward a life of raising cattle and tending herds. However, Sterling’s career would soon change as violence from the revolution in Mexico spilled across the Rio Grande.

In 1915, as World War I raged across Europe, another war was being waged closer to Texas. Beyond the Rio Grande, violence spread throughout Mexico in a bloody civil war. At the height of the conflict, Mexican forces raided American cities and military outposts, incurring the wrath of the famous Gen. John J. Pershing and his 10,000-man punitive expedition.

As Pershing pushed deeper into the heart of Mexico, hunting Gen. Francisco Pancho Villa, violence continued along the Texas border. There, Sterling found his calling as a scout and reserve member of the United States 3rd Cavalry Regiment and Texas Rangers. Working closely with both groups, Sterling saw firsthand the slaughter of more than 500 Texans at the hands of Mexican troops. As the raids worsened, word spread of the “Plan of San Diego,” a plot that called for race riots between Anglos and Tejanos. These riots were to be ignited by bloody incursions from Mexican seditionists. Supporters of the plan believed the riots would eventually force America to return the Southwestern states to Mexican control.

Fear of the Mexican reoccupation plot was growing as the Zimmerman Telegram arrived, both at the height of the U.S. march to World War I. The telegram offered Mexico help in conquering most of the Western United States in exchange for allying with Germany and possibly Japan. The plot called for the extermination of all Anglo men over 16 and any Latino that fought against Mexico. Texas’ response to this threat came from a combination of soldiers, rangers and deputized citizens who left nearly 1,000 of the Mexican seditionists dead.

As the Texas border came under control, the United States prepared to join the European war effort. Sterling, like many Americans, joined this effort, commissioning with the Texas Infantry as a second lieutenant. Though he never served overseas, Sterling's time with cavalrymen on the border helped him prepare newly enlisted soldiers for the war.

After the war, Sterling returned to law enforcement as the sheriff and justice of the peace of Mirando City, a border town near Laredo. He once again worked alongside the Texas Rangers, whose duties had shifted from fighting Mexican revolutionaries and seditionists to catching bootleggers smuggling liquor across the border.

“Bill [Sterling] preserved order in an oil town by methods learned from the Texas Rangers and other border officers. On an unpainted pine shake we found a large sign bearing ‘W.W. Sterling, Justice of the Peace, The law of the Tex-Mex,’” described contemporary historian Walter Prescott Webb. “Nearby, stood a boxcar in which the judge held his prisoners by means of a generous length of chain and padlocks.” This method of restraint was called a “trotline.”

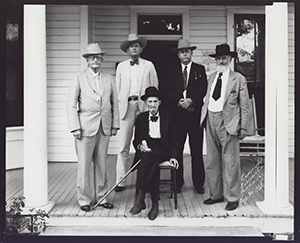

Adjutant General William Sterling poses with his Texas Ranger Captains.

Adjutant General William Sterling poses with his Texas Ranger Captains.

As crude oil gushed from derricks rising against the bright Texas sky, the call went out for roughnecks seeking “black gold” to move to Borger, a city centered in the Texas panhandle. Though every oil town had its share of card houses and lawlessness, a corrupt city government coupled with a population increase of more than 40,000 people in three months, allowed prostitutes, card sharks and bootleggers to become nearly as common as oil workers. Lawlessness in Borger reached a boiling point when murders and explosions within the city limits had become a way of life.

“Many persons have been killed including several officers and two or three women. Daylight robberies, hold-ups, explosions and bootlegging continued practically unabated,” according to a contemporary Associated Press report.

Sterling arrived under the command of Capt. Frank Hamer, who would later become famous for putting an end to Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s criminal careers in a hail of gunfire. Working with 10 other Rangers, Sterling and Hamer brought the town under control as Rangers arrested 124 men within the first day. Each lawbreaker found himself shackled to a trotline awaiting removal to trial in Stinnett, Texas. Rangers also targeted vices throughout the city, issuing warnings to 1,200 prostitutes to leave town or face arrest. Liquor, gambling and corruption were additional focuses of the team as it sought to reign in the lawlessness of the city.

“The liquor traffic was broken up, many stills being seized and destroyed, and several thousand gallons of whiskey captured and poured out. 203 gambling slot machines were seized and destroyed,” said Brig. Gen Robert Robertson, the Adjutant General of Texas at the time. “As a result of the demand on the part of the citizens of Borger for administration of the law, the mayor, city commissioners and chief of police resigned, replaced by citizens pledged to uphold laws.”

Sterling’s work in Borger did not go unnoticed. Among other changes, he would promote Sterling to captain, giving him command of the Laredo-based Company D.

His previous experience on the border allowed Sterling to run an efficient unit far from the headline-grabbing troubles of the booming oil towns of northern Texas. He worked with his Rangers to respect the local population and to be sympathetic to Anglo and Tejano concerns, fairly administering justice. For a time, Sterling seemed to have settled into a job he had always wanted. This changed after the election of Ross Sterling to governor.

Ross Sterling prepared to take office as the nation was entering the Great Depression in 1931. The economic collapse of the nation would ruin many of his initiatives in the legislature, but the one initiative in which he did find support was strengthening the Ranger corps.

Ross Sterling had known Bill Sterling for years, having met through Bill’s father. Both men discussed their ancestry sufficiently to decide there was no kinship, a determination that would be important as Ross Sterling prepared to appoint his new adjutant general for the Texas Military.

“I called in William W. Sterling, a tall, colorful Ranger captain, and gave him the names of several men who had applied and asked ‘Whom would you suggest for adjutant general?’ Bill replied that he would like to see Torrance of Fort Worth get it, but he could get along very well with any of those mentioned” said Ross Sterling. “I told him you won’t have to get along with any of them. I’m going to appoint you.”

With that conversation and a state senate confirmation, Capt. Bill Sterling became known as Gen. Bill, the first adjutant general pulled from the Ranger corps since Texas became a republic. If anything signified the unique path of his ascension, it would be his choice in uniform.

Though he served as a commissioned officer during WWI, Sterling left mandarin collars and olive drab to career Guardsmen. The 6-foot-3-inch Ranger instead donned his trademark gun belt with a revolver inscribed, “Captain Sterling,” on the handle. No stars adorned his uniform; instead he had “GENERAL BILL” stitched above the pocket of his western shirts along with western motifs of bucking broncos or lone cattle.

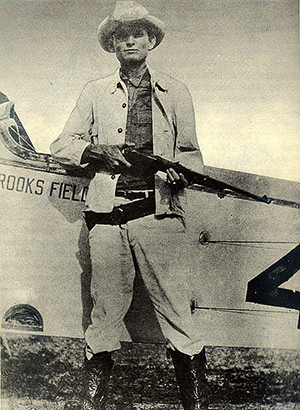

Brigadier General William Sterling posing with a rifle at Brooks Field, a former U.S. Army airfield located outside of San Antonio, Texas. Members of the Texas National Guard participated in pilot training for both fixed wing aircraft and blimps in the 1930's.

Brigadier General William Sterling posing with a rifle at Brooks Field, a former U.S. Army airfield located outside of San Antonio, Texas. Members of the Texas National Guard participated in pilot training for both fixed wing aircraft and blimps in the 1930's.

Sterling took office vowing to eliminate politics from the promotion system within the department. Changes to the National Guard’s structure began with the 1903 Dick Act, giving the organization a standardized promotion system within the Guard. However, the Rangers still primarily promoted individuals under a system patronage and political influence. Sterling issued regulations requiring all captains of Ranger companies to serve first for two years. He also directed promotions to occur on merit and the reputation of the candidate.

Trouble from oil towns mostly sprang from vices that followed oil booms and roughnecks from drill site to drill site, but July 1931 would see oil producers for the first time fall under the gaze of both the Rangers and the National Guard.

The railroad commission moved to regulate the oil market and implement production limits but found the task impossible without an enforcement arm. Ross Sterling, an oil man before his political election, knew the problems collapsed oil markets would add to the stagnant economy of the depression era. He called upon his adjutant general and informed him it was time to restore order to the oil fields.

Ross Sterling declared martial law across the oil fields, deploying 1,200 National Guardsmen from the 56th Calvary Brigade to Southeast Texas, led by Brig. Gen. Jacob Wolter, an expert in population control. Gen. Sterling empowered the Rangers to arrest any producers defying orders from Guardsmen to shut down drilling operations.

The deployment of the Rangers was more than enough to enforce the newly issued production limits. Without a single shot fired, Guardsmen secured the largest-known reserve of petroleum in the world at the time. However, this would not last long. Court injunctions issued in response to lawsuits by oil producers found the occupation to be unconstitutional. Therefore, as quickly as they arrived, the National Guardsmen left the area.

Oil towns would continue to plague Bill Sterling’s time as adjutant general. However, a new foe would soon emanate from Oklahoma.

Bill Sterling saw his tenure as adjutant general come to a close in 1933. Ross Sterling lost his bid for the Democratic nomination to Miriam Ferguson, and, as a result, the governorship. Though the Rangers began an investigation into claims of ballot stuffing on the part of the Ferguson campaign, Ross Sterling called the investigation off in order to avoid the appearance that he was using the Rangers to influence an election.

Bill Sterling knew Ferguson’s retaliation for the Ranger investigation into election tampering would be fierce, so he tendered his resignation before she took office. Upon his departure, Sterling’s biennial report to the governor offered some parting guidance about the Rangers’ role in the Texas Military.

“The Ranger service should be taken out of the hands of the adjutant general, who in almost every case is a military man. The military organization of the state has grown to such an extent that the adjutant general should devote his entire time to the military.”

It took another two years for Sterling’s vision for the Rangers to manifest as the force moved from the Texas Military’s control to their new home at the Department of Public Safety. Now part of an official state-sanctioned law enforcement agency, Rangers saw their department grow into a modern investigative force with tools and methodologies at their disposal that their predecessors could only imagine.

The Rangers left the Texas Military Department, and along with it, they left behind a joint legacy of heroism and the story of Texas’ only Ranger-adjutant general.