By David Brown, 1LT, Texas State Guard

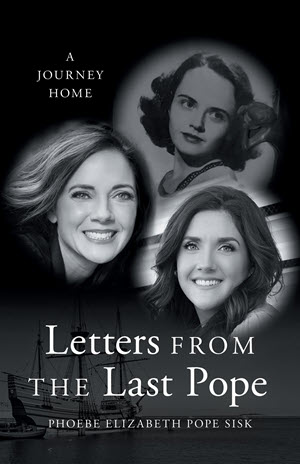

DALLAS – In the military, the virtues of leadership and duty are often highly celebrated, while mental health is less often discussed. But a new memoir by a Dallas-based officer in the Texas State Guard is both a stirring account of resilience amid the mental health struggles of a family member and a powerful reminder of how mental wellness can bolster military preparedness. “Letters from the Last Pope” by Texas State Guard Capt. Phoebe Sisk (née: Pope), explores the ripple effects of her mother’s suicide and the persistent stigmas surrounding mental illness.

DALLAS – In the military, the virtues of leadership and duty are often highly celebrated, while mental health is less often discussed. But a new memoir by a Dallas-based officer in the Texas State Guard is both a stirring account of resilience amid the mental health struggles of a family member and a powerful reminder of how mental wellness can bolster military preparedness. “Letters from the Last Pope” by Texas State Guard Capt. Phoebe Sisk (née: Pope), explores the ripple effects of her mother’s suicide and the persistent stigmas surrounding mental illness.

“My dad told us she went to sleep and didn’t wake up.”

That’s how 5-year-old Phoebe Pope learned about her mother’s suicide. The youngest of 12 kids, Pope’s family fell upon hard times following the tragedy of her mother’s death and had relatively few possessions, living in a home in Fort Worth that was in a constant state of disrepair. “For years we didn’t have heat or air conditioning, nor did we have a refrigerator or stove…” Her parents were artists, money was tight, and fights between them, unfortunately, grew more and more common in Phoebe’s early years.

While certain first childhood memories were full of love and wonder created by her creative and maternalistic mother, later memories took on the trauma of her mother’s mental health decline and include the day her mother threw the garbage into the front seat of the family car; as well as being left alone at night on a bus bench at 4 years old; and police visits to her grandfather’s home to recover her and her siblings on occasions when her mother swept them away from the family home in the middle of the night.

Phoebe’s father struggled as a single parent to maintain the home, especially after the worsening of her mother’s mental health that resulted in her taking her own life. Being a lone wolf, Phoebe’s father wasn’t prone to reach out for help and had very few friends with whom he interacted, creating a sense of isolation for the family. While Phoebe and the youngest siblings felt respected, valued, and included in their small Fort Worth schools, they were aware of whispers from concerned mothers in the community, and that “we kept our lives secret - we didn’t talk about it. We couldn’t help but feel different.” Sisk says.

Today, as a Captain in the Texas State Guard, a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, and the author of a new book on mental health, Sisk is leading the way in discussing mental health with candor and honesty.

“In anyone’s story, you see a part of your own,” Sisk says. In Sisk’s story, many readers will recognize the feelings of shame and isolation that often accompany tragedy, poverty, mental illness, and other difficult life challenges, just as they will also recognize the same inspiring resilience that allows us to overcome overwhelming odds. “We don’t rise up despite our stories, we rise up because of them,” says Sisk.

“We didn’t think of our lives as tragic at the time, it was just our normal,” Sisk says about the experience of growing up a painfully shy child in a family where one beloved parent was gradually and heartbreakingly lost to the family due to mental illness. After her mother had a wrongful hysterectomy, episodes of manic depression became more common. Her parents divorced, and her father did the best he could to insulate the kids from their mother’s struggles. “He really never talked about my mother’s suicide,” Sisk recalls. “He always spoke well of her... always light, never dark. Much of what I knew about my mom I learned through stories my siblings would share or my father’s memories of her. I didn’t even know the truth about my mother’s death until after my son was born.”

According to research published by the National Institutes of Health, the impact of parental mental illness can affect children in a variety of ways, ranging from social deficits characterized by difficulties in work or marriage to issues related to poor self-esteem, and social adjustment. Many kids from such backgrounds have negative experiences in their childhood including abuse, neglect, isolation, and guilt. But Sisk says having a father who believed in her and strong, supportive relationships with teachers resulted in her developing a sense of self that kept her true to her talents and interests–albeit in a private way.

Sisk signed up to work on the school paper and joined the band. Her enthusiasm for school cleared the way for her to skip a grade, graduate early and enter junior college at age 16. Later, at Austin College, Phoebe met Kevin, the man who would become her husband and her inspiration to join the U.S. Marine Corps. After 4 years of federal military service, the Sisks embarked on careers in business and education; later starting a real estate firm, and raising two kids of their own (Elijah, 21, and Sarah Katherine, 19).

“Teaching kids and mentoring others made me realize that as people, we rise up to others’ expectations- and that confidence, optimism, and our belief in others are often self-fulfilling prophecies,” Sisk says. “Encouragement is often overlooked, but all of us, at one point or another, influence others in ways we do not know. We all need to acknowledge that, at some point, we’ll be playing that role.”

Sisk found herself playing just such a role in 2021 at a Texas State Guard leadership conference (one of the many educational opportunities available to service members) in her presentation of spiritual mentoring, a sharing that acknowledged the gifts of both intellect and spirit that we impart on others, often with no awareness of the fullness of the impact.

Sisk’s presentation at that conference was powerful, says Brig. Gen. Roger Sheridan, who now commands the 6th Brigade, Texas State Guard. “It gave leaders at all levels a greater capacity to express themselves and a greater capacity for understanding others. And the more we understand about others, the better we can do ourselves.”

Sisk’s message fits squarely within the Guard’s “mission-ready” imperative, according to Capt. David Arnold, who serves in the Texas State Guard’s T3 (operations) section. “Whether we’re responding to hurricanes, on a security support mission, or some other emergency…we have to be able to know that we can meet our objectives, and that requires resilience. We need to be able to talk about it–and train on it.”

Though earlier in her life Sisk had been reluctant to speak about her experiences, the pandemic lockdown inspired her to slow down, to take stock of all that she had overcome, and to encourage others not to be defined by the same stigma, shame, and tragedy that had bound her for years. This realization would serve as the inspiration for “Letters From the Last Pope: A Journey Home” (Scribe Publishing), her memoir aimed at encouraging others to embrace the power of personal transformation through intentional awareness and “radical compassion” to overcome a painful past.

In her book, framed as 26 stirring ‘letters’ to people who have altered her own life’s trajectory, Sisk explores the concept of epigenetics: how behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way one’s genes work, and thus how unhealed trauma can affect a family for generations.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, epigenetic changes can alter how the body reads a DNA sequence - but unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes are reversible. The book, Sisk says, reflects a realization that “we’re meant to share our stories.” It is, as Sisk explains it, a kind of “spiritual mentorship” that sets the example for others to do the same, with enormous healing potential.

“We carry shame and so we don’t tell our stories. But we’re meant to share so that we can begin the healing process - not only for ourselves but for someone else. That’s the most beautiful part of it, looking at the past through a lens of grace. Those things that happened made us into the people that we are. There are no ‘mistakes’ in that story. There’s a beautiful thread that will reveal itself – though it’s sometimes hard to see in the middle of pain and challenge.”

Rising from family tragedy, the author offers a moving, often poetic first-hand account of a little girl who grew up to become not only top of her class in college, but a gifted educator, author, businessperson, public servant, and parent. In “Letters from the Last Pope”, Phoebe Sisk outlines an arc of redemption made possible by embracing mental health with honesty and candor, overcoming ancestral trauma, and building a new future.

“It makes a lot of sense that we do the work, so our kids don’t have to.”

Sisk serves in the T3 (operations) unit of the Texas State Guard Headquarters and Headquarters Company (Camp Mabry/Austin), and is an adjunct to the T7 (training) staff.

As a branch of the Texas Military Department, the State Guard provides mission-ready military forces to assist state and local authorities during emergencies and augments the Texas Army National Guard and Texas Air National Guard as required. “It’s good to be around purpose-driven people,” Sisk says, noting the diverse skills and backgrounds of her colleagues in uniform, and the selfless sacrifice service members undertake on behalf of their fellow Texans. “There’s a sacredness to their service,” Sisk adds.

The Texas State Guard is looking for healthcare professionals, lawyers, teachers, engineers, and others willing to make a commitment to serving their fellow Texans. Though many members of the State Guard have prior federal military experience, it is not a requirement for service. More information about opportunities in the Texas State Guard can be found online at tmd.texas.gov/state-guard.